Militaries Race to Cover their Tracks in Light of Strava Scandal

A fitness-tracking app is revealing sensitive information about military bases, personnel and supply routes via its global heat map. The ANU student who uncovered the major security oversight explains.

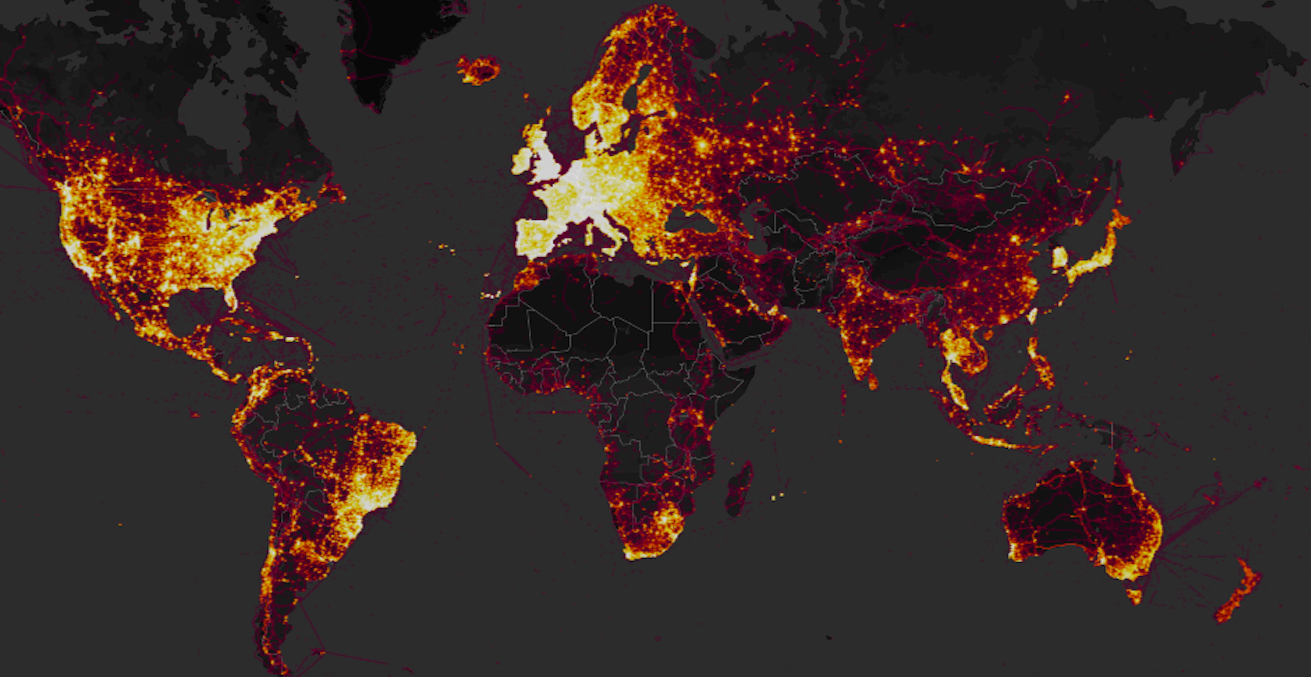

Strava is a ‘social network for athletes’. Over 27,000,000 users around the world have signed up to track, share and analyse their fitness goals and their activities. Last year the company released a map containing more than three trillion data points spread over almost 30 billion kilometres. The result is a dazzling galaxy showing mountain trails, bike lanes and footpaths all over the world.

Hidden in the array of data is a trove of secret military bases and classified information related to the militaries of many countries. The data reveals the location of multiple secret US bases and outposts used to train and advise local partner forces in the fight against Islamic State; the location of French bases used in their deployment to the Sahel region of Africa; the UN peacekeeping bases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the suspected Russian patrols protecting an airbase in Syria; and even the flight deck of the HMS Queen Elizabeth. Notoriously clandestine, these are now mapped in unprecedented detail.

Armed forces have strict guidelines on where and how enlisted personnel can share their location. Indeed, operational security is one of the key tenets in the modern battlefield. Failures in this realm have haunted soldiers in recent years; Russian troops in Ukraine and IS fighters in Raqqa come to mind. The locations of these soldiers were discovered through stray mobile communications and revealing photos.

Strava’s map has amplified this strategic mishap. The heat map does not just show sporadic snapshots of soldiers’ locations, it displays regular jogging trails and patrol routes. As a result, detailed maps of military bases that the US government has never publicly admitted the existence of have been exposed.

It is possible to opt out of data sharing with Strava. It is also possible to set up private zones in which recorded activity would not be shared. It appears that many soldiers have failed to select these settings. As a result, covert military bases light up across the world’s war zones from Mali to Syria to Afghanistan.

Where the app enjoys popularity, it is impossible to tell whether a track is military or civilian due to the anonymity of its data. However, in many war zones the app is far less popular. Military bases across those regions light up like a Christmas tree. In areas of known access restrictions to civilians, such as the main US army base in Seoul, it is possible to map out military infrastructure in unprecedented detail.

The data allows us to infer pattern of life details, because the frequency of usage along routes is clear. It is possible to see which buildings and areas within a base have the highest concentration of forces and would make the most significant targets. This information would be impossible to discover, especially for adversaries in hostile territory.

In the days following the map’s discovery, further vulnerabilities in Strava’s data privacy were exposed. These discoveries signify an acute security risk to active duty soldiers and other deployed sensitive individuals. By leveraging the public data, it was possible to identify the personnel running along a particular route. Near the military base next to Mosul Dam in Iraq is a display of the profiles of individuals who run a regular route along the base’s perimeter. Those that had linked social networks allowed them to be scrutinised further. This identified them, and also listed the other locations where they had used Strava. In many cases this method could be used to find countries’ intelligence personnel.

As non-state actors and weaker state adversaries begin to acquire more precise methods of targeting, the ability to cause significant damage before getting targeted by counter measures will increase. Until now, these groups had to acquire accurate and detailed intelligence using covert operations. Strava publicly provides this information and thus represents a change in international warfare.

The revelation of this data caught most governments off guard. In Australia, the government and security services were informed of the data leak before it received significant media interest, but remained unaware that this data was accessible to the public. With this information, it took slightly over a week before any instructions were given to enlisted soldiers on how to negotiate the possible data breaches.

Deployed personnel were similarly caught unawares when the story received media attention. The US has responded by committing to develop additional policy. Indeed, Trump’s cyber security coordinator of the National Security Council, Rob Joyce, referred to the revelation as forcing “all to look at risks of big data analytics.” Another country’s Special Operation Forces deleted their Strava accounts and disposed of their Fit-Bits after hearing about the data breaches.

For now, Strava has prevented the mining of individual data from its platform and has taken some effort to remove the data available in sensitive areas such as Syria and Iraq. It is unclear how the company aims to address this in the long term, considering that the ability to compare activities in an open way against other athletes is a core premise of its platform.

Strava will not be the last device with similar implications and merely banning the use of these devices will do nothing to hinder the threat posed by those technologies yet to come. This data breach shows the challenge of big data and technologies that allow any trained individual to leverage digital information in a way unintended by those who produce it. More seriously, these technologies could be developed into products with significant implications for national security.

The line between personal convenience and operational security poses challenges for the armed services and the national security community in the future. The Australian armed services need to have an increased awareness of this challenge—at all levels—in order to prevent a similar situation in the future, and a leak with perhaps much more significant implications for force protection.

Nathan Ruser studies international security with a double major in Middle Eastern studies at the Australian National University in Canberra. Earlier this month he was responsible for revealing the capacity of the Strava app to expose the location of military bases and personnel globally.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.