Can Australia Learn Anything from China?

China is advancing in many areas of technology and the economy, and has emerged as a world-class innovator. With the US less predictable and collaborative, can Australia learn from China?

Western complacency is hard to shake, but every now and then a jolt interrupts the slumber, such as when Chinese automaker, Build Your Dreams (BYD), overtook Tesla as the largest producer of electric vehicles. More recently, the Chinese artificial intelligence model DeepSeek shocked with its capability and the speed and low cost of its development, sending Nvidia’s shares down by approximately AUD$948 billion.

Is it time that the West reassessed its attitude toward China? The urgent question now may be, can the West learn from China? This simple question may challenge the world view of many, but the West’s conviction of its own moral superiority does not guarantee its continued global dominance.

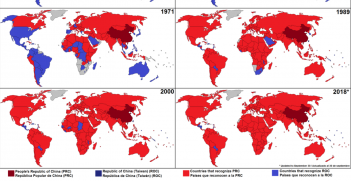

A Western sense of moral superiority based on notions of universal values has historically combined happily with economic, military, and technological dominance. For example, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Critical Technology Tracker, in the five years to 2007, the US led the world in 60 of the 64 critical and emerging technologies, and China led in three—a good reason for Western self-confidence. Fast forward to 2023 and the US leads in just seven, while China leads in 57. Furthermore, China produced five times more high impact research papers than the US. It may be hard to accept, but Western self-confidence without merit is smugness. The ancient Greeks in their tragedies wrote about hubris as the reason for the downfall of the great. There is a real danger that we are witnessing a tragedy of that nature on a global scale.

China is also forging ahead of the West on infrastructure. For example, once the glittering symbol of international modernity, US trains and roads now suffer by comparison. Search for images of the New York subway, and one is reminded of its launch in 1904, with many fundamentals, such as platforms, unchanged in over a century. Similarly, US roads and bridges are in such dire straits former President Joe Biden allocated over a trillion US dollars to modernise US infrastructure.

Admittedly, China has the advantage of recent subway construction, and so naturally much of it looks more modern than the US’s. China also has the world’s longest subway system, with over 11,000 kilometres, making it impressive in size, scope, and appearance. Even more starkly, China has over 47,000 kilometres of very fast train tracks, double the rest of the world combined, and achieved in around two decades. Early Western sneering at presumed inferior Chinese build and safety standards have been muted by China’s positive experience. Even dismissing this achievement as possible only because of China’s statist approach rings hollow in a world where the EU has been enaging in state subsidies and trade protection (much to the disadvantage of Australian farmers), and President Donald Trump has touted tariff-based industry protections as appropriate policy responses. The issue on infrastructure is that China has been more successful than the West.

China’s success can also no longer be explained by intellectual property theft and industrial espionage. Having done research on a Master of Laws paper on China’s protection of intellectual property during a residency in Beijing, I can confirm that China played loose and free with IP while it was developing, at the expense of Western companies and governments. However, that hardly makes China unique. At the start of the industrial revolution, the biggest and most egregious infringer of IP rights was the US, much to the chagrin of the UK, which led the world in patents for industry and copyright for books. The US celebrated the common language by making free use of all the IP it could take, and its subsequent industrial dominance of the world is well recorded.

Nonetheless, China’s systematic infringement of IP is certainly a cause for grievance, but China has moved to being an innovator more than copier of innovation. These days, when China’s industrial espionage capabilities trawl the West, it is often a benchmarking exercise to confirm China’s lead in so many of the world’s important technologies. China is now a global generator of intellectual property, and a belief that China succeeds only because of stealing innovation from the West is outdated. Hence, the question the West should ask itself is not whether it can learn from China, because clearly there is much it could learn from a China that is now a world-leading innovator, and indeed, a source of valuable intellectual property, which it is often prepared to share, including artificial intelligence. The real question is whether the West is willing to learn from China, and that seems several steps along the grief cycle from where the West is now. Unfortunately, even raising such a question is likely to provoke strong reactions, particularly from far-right commentators and segments of the Murdoch media, who, much like the sheep in Animal Farm, may resort to chanting dismissive terms like “panda-hugger.” Such rhetoric is reductive and polarizing, but it reflects the broader challenge of fostering nuanced policy discussions. This is regrettable, as there is a serious conversation that needs to take place at all levels of Western governance.

I have the advantage of having worked constructively with Chinese officials when mutual benefit was possible, and having strong disagreements with them when negotiations were difficult and when push-back on China served a purpose. Australia’s interests would now be advanced by a meaningful and detailed public reassessment of Australia-China relations.

David Livingstone is a former Australian diplomat.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.